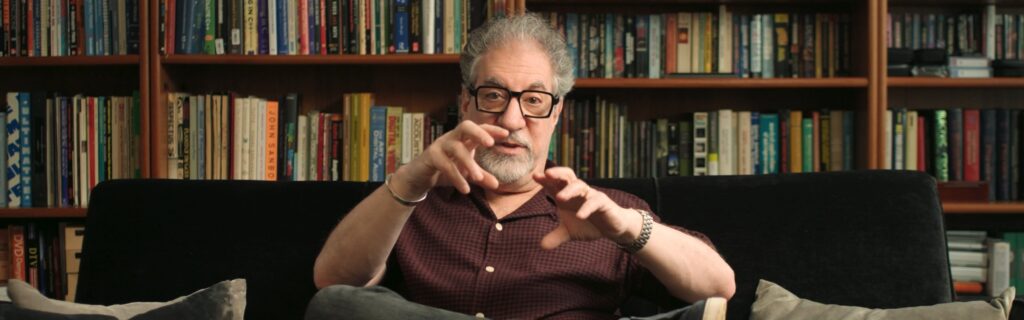

Customer Profile

Dean Winkler: Crafting Video Art with Adobe After Effects and iodyne Pro Data

In this video we take a look at how video artist Dean employs iodyne Pro Data SSDs to handle the heavy demands of his high-res, data-intensive compositions. 24TB Pro Data at Thunderbolt speeds, paired with Premiere Pro and After Effects, allows Dean to effortlessly layer complex compositions and render stunning visuals in real time without proxy workflows, enabling him to focus purely on his unique creative vision.

Dean Winkler, a pioneering video artist, is known for pushing the boundaries of workflows within Adobe After Effects®, by combining analog techniques with cutting-edge technology. His unique style, “structured improvisation,” merges computer graphics with synthesizer spontaneity.

Based in Tribeca, New York, this film and TV engineer has worked with legends like Philip Glass, Nam June Paik, and Laurie Anderson, making a serious mark on the industry. Dean has watched video tech grow from the clunky analog days to today’s digital magic.

We sat down with Dean to learn about his latest film “In C, Too” which premiered at Slamdance, and learn how his workflow has evolved over the years.

How did you begin your journey into the world of video art and post-production?

My story starts at VCA Teletronics in the 1980s, one of NYC’s first video editing spots. With the industry’s latest, top-notch gear at my fingertips, I would mess around on weekends, creating visuals that blew people away.

My first piece, “Modulated Horizontal Line,” set to Terry Riley’s awesome music, was just the beginning. Throughout the ’80s, I teamed up with many famous artists, experimenting with post-production effects that were way ahead of their time.

My style is a little unconventional. I’m all about old-school editing but love layering stuff together in one go, pushing hardware and software to their limits. My current process involves dancing between Premiere, After Effects, and a whole suite of plugins to achieve what I’m after.

What is your workflow like? How has it changed over the years since you first started?

My workflow is a bit unusual, in that it’s modeled on how we used to create abstract video art using linear post-production edit suites.

In the linear editing days of old, I would take six NTSC playback and one record video tape recorder, four channels of digital video effects devices, and a large Grass Valley Group switcher, layering together as much as possible in one pass. Feeding the DVEs back into themselves created unexpected, non-linear images.

To control everything in real time, I built custom interfaces to the CMX that allowed for time code-based triggering of many analog parameters. When we had setups we liked, we recorded that pass onto videotape. That videotape would then be used as playback in the next pass.

Now, we do something called “Structured Improvisation”.

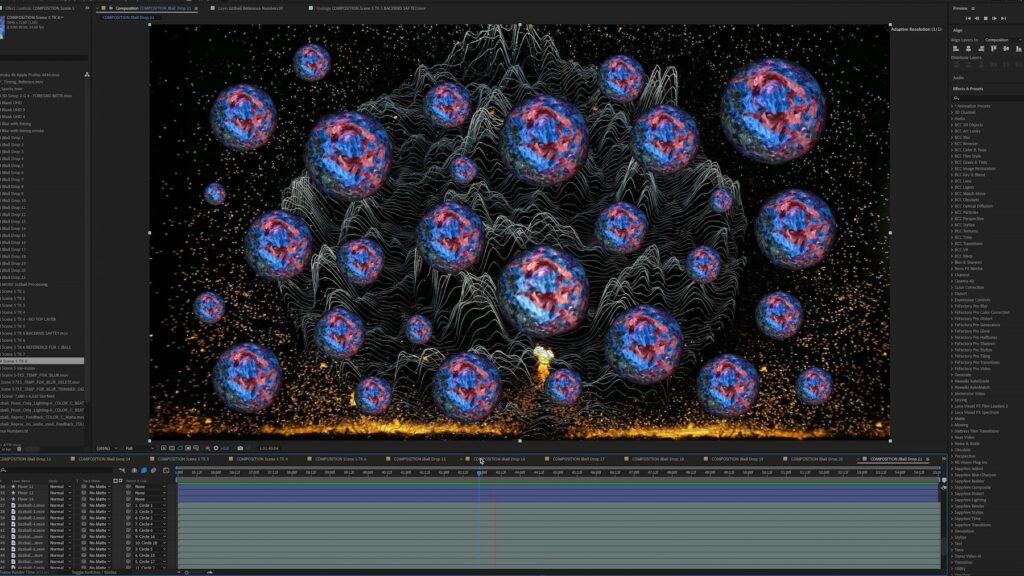

Because we want the image possibility you get from more of the computer graphics world, but we want the jazz improvisation of the synthesizer world, we tend to push programs to places they’re not meant to be. The DVEs and analog switcher of the olden days have been replaced with Premiere Pro, After Effects, a speedy iodyne Pro Data SSD, and a host of plug-ins and generative process hacks.

So that can be plug-ins where we make weird variables. We take After Effects and Premiere into their nonlinear regions. We get them to make weird images. We record them, and then we layer them back on top of themselves. And unlike in the analog world, where at best at the end I was doing 50 layers, now I can do a thousand layers thanks to modern hardware and software.

“What the iodyne and Creative Suite combination gives you is that much more real-time design potential. Together, it’s seamless. It disappears and it all works.”

How do you switch between After Effects and Premiere Pro in this real time, improvised creation process?

After Effects and Premiere Pro are critical because that’s how I was able to light, and layer and build everything. Now, once we have our basic images, I often would go off and really flowchart how they would have to get layered together to get the lighting right, to get the kind of levels of subtlety, particularly like say in the opening where you see those beautiful lit dark things.

The connection between After Effects and Premiere Pro is really great because you can set up a bunch of elements in After Effects and immediately look at them in your cut without having to output them, which is really handy.

For my latest video art film “In C, Too,” created with John Sanborn, I applied the same principles of our Structured Improvisation techniques, but this time using an iodyne Pro Data SSD storage solution for both image playback and recording.

Why do you need an external storage solution like iodyne Pro Data?

When working on these projects, the software is pushed beyond normal parameters into non-linear regions to give unexpected results. Hardware control of analog parameters has been replaced with keyframe control—at the expense of having to render instead of outputting in real-time.

The key to this workflow is being able to have multiple streams of extremely high-quality source video at once coming into the machine. I can’t work with proxies in this workflow because when you’re forcing these programs to go into their nonlinear regions and do things that they’re not designed to do, nothing would be repeatable. You only make that image at that resolution at that file format, and you have to have enough data rate to be able to do that for multiple streams. That’s the key to using iodyne. It’s the only Thunderbolt-based product that has that kind of throughput.

The iodyne Pro Data connected to my Mac Studio allows me to work on each pass at full resolution UHD 3,840 x 2160 with multiple video streams of ProRes 4444. When I run out of processing throughput, I simply record the results to the iodyne Pro Data and then use it as a playback source for the next layer. Setup parameters don’t drift, and noise build-up is minimal, allowing some shots in the film to have almost 1,000 layers. It’s seamless, and it all just works.

The awesome speed of iodyne Pro Data and the robust capabilities of Adobe’s Creative Cloud apps all seamlessly work together as I push them to their limits. The software and hardware sort of disappears into the background so I can fully focus on my art without any technical roadblocks.

Dean Winkler’s “In C, Too” premiered at the Slamdance Film Festival in Park City, Utah and is making the rounds at other film festivals around the world. You can check out other projects of Winkler’s on his website.